Summary

- Decentralized Finance (DeFi) refers to the range of financial services that exist on public blockchain networks.

- DeFi is rapidly evolving with insufficient transparency, a lack of shared awareness about its risks, and methods to measure and mitigate those risks.

- A cohesive risk assessment framework that enables timely measurement of risk for a particular protocol and allows for a comparison of risks across protocols would help facilitate informed investment decisions in the space.

- In this article, Moody’s Analytics and Gauntlet hope to promote further understanding about this exciting and growing area of finance and begin to chart a path forward toward a common framework for risk assessment in DeFi.

Whether you view cryptocurrency as the future or a fad, there is no question 2021 was crypto’s breakout year, and although we cannot predict how the market will evolve going forward it seems clear that crypto will have a lasting and transformative impact on the financial system. A notable success in the space has been the rise of decentralized finance, or DeFi – a novel, rapidly growing component of the crypto and financial ecosystems. As real fixed-income yields have remained persistently low, many investors have looked to crypto in the hunt for yield, with offerings for staking, participation, and funding greatly exceeding offerings in the traditional financial sector. Although the purported returns are attractive, how do we measure risk in this new and rapidly changing environment?

In traditional finance, we rely on the time-tested understanding of micro- and macro-economic structures to evaluate an obligor’s risk and creditworthiness. However, DeFi is rapidly evolving with insufficient transparency, a lack of shared awareness about its risks, and methods to measure and mitigate those risks. By collaborating in writing this article, Moody’s Analytics, drawing on over a century of expertise in risk measurement, and Gauntlet, a leader in financial modelling and simulation for crypto assets, hope to promote further understanding about this exciting and growing area of finance, and begin to chart a path forward toward a common framework for risk assessment in DeFi.

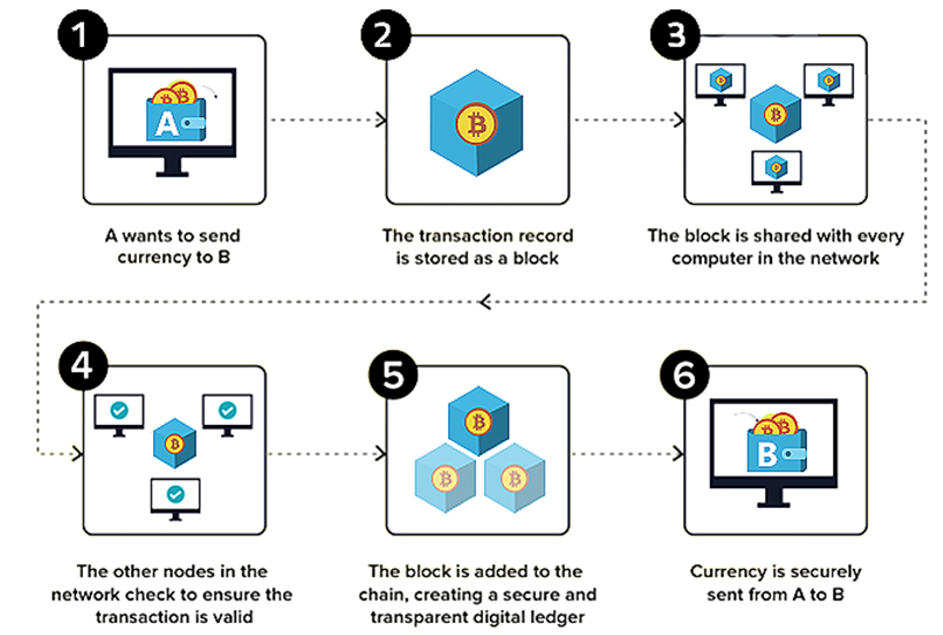

Blockchains are the core infrastructure of cryptocurrencies, acting as a digital, immutable transaction ledger stored on a distributed network. Each transaction is recorded in a “block” which, once filled and validated, adds to a growing chain, with each storing a one-way hash of the previous block. A network of validating servers continually adds each new block to the chain via consensus, eliminating the need for institutional middlemen and associated prerequisites, such as business hours, settlement and clearing.

Many blockchains natively support “smart contracts” to implement the terms of a transaction. Smart contracts are not contracts in the legal sense that we are accustomed to in traditional finance. Rather, they are computer programs deployed and stored on blockchains designed to self-execute when certain conditions are met. Since they exist on the blockchain rather than on a specific server, their code, execution logs and function are distributed, fully transparent, and irreversible. The smart contract paradigm allows conditional transactions – akin to real-world contracts and escrow services – to be conducted without central controlling or clearing mechanisms. This represents a significant evolution in decentralizing financial transactions, paving the road for the creation of DeFi.

DeFi is a catch-all term referring to the range of financial services that exist on public blockchains that mirror the kinds of services that exist in the traditional financial system: borrowing, lending, asset creation, and more. It uses smart contracts to eliminate the need for a trusted intermediary to facilitate transactions, allowing anyone to transact on these protocols, which in this jargon, refer to the ecosystem centered around decentralized applications like smart contracts or a grouping of them that mirror traditional financial functions. Some current prominent examples include automated market making, lending protocols, and option exchanges.

Why does this matter?

As of December 2021, the top 100 DeFi tokens have a combined market capitalization of nearly $100 billion, with many forecasting strong growth in the sector to continue. Despite the rapid expected growth, the regulatory uncertainty and difficulty so far in properly modeling risk has left many potential market participants waiting on the sidelines. In many ways, the latter remains a paramount task. As the worlds of DeFi and traditional finance continue to converge, how do we understand risk in this new paradigm? Quantifying risk is essential to assess whether institutions are following risk best practices, and at a macroeconomic level we cannot properly understand the risks that the crypto ecosystem may pose to the larger financial markets without a risk assessment framework.

As DeFi has gained the attention of traditional financial institutions globally, it is likely we will see continued convergence due to the high complementarity between traditional financial services and DeFi. The low friction and transactional atomicity provided by decentralized applications may be a boon for certain financial service segments and may replace others. Whether we are seeing a true paradigm shift or just the emergence of a new technology, the first step is certain – we must be able to properly evaluate the benefits and risks of decentralized finance.

How does DeFi work?

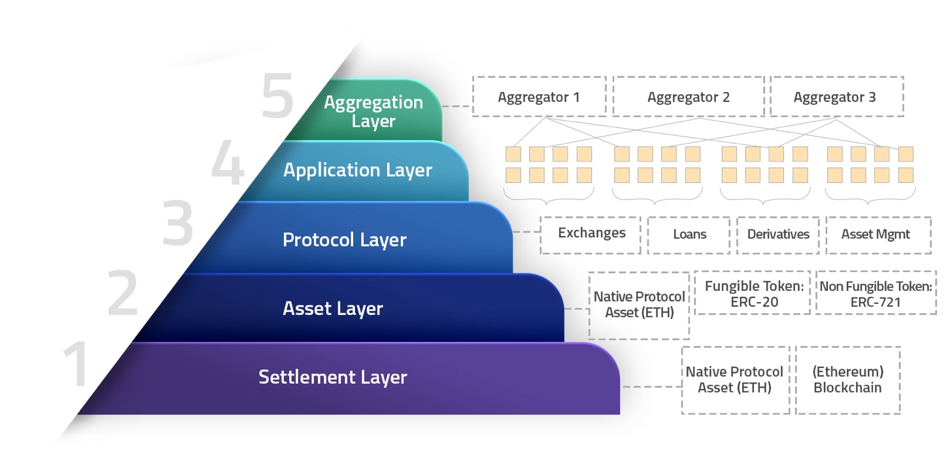

Typical DeFi platforms can be subdivided into layers, representing its core attributes:

- The settlement layer handles the settlement of transactions between parties interacting through the DeFi application. This is handled by the base blockchain that the protocol is built upon. While the most common blockchain for DeFi is Ethereum, new blockchain protocols such as Avalanche and Solana have emerged as visible contenders.

- The protocol layer is the code and smart contracts comprising the protocol, which govern how the protocol operates.

- The application layer is the front end which end users interact with, usually via browser extension or application.

- The aggregation layer is akin to financial building blocks in DeFi, allowing assets and products to be used and combined without explicit agreement or permission. For example, a yield aggregator protocol displays real-time yields across different assets and protocols.

Composability is a novel and enticing aspect of DeFi. As smart contracts are largely open source and by nature publicly visible, developers can easily access and connect to different applications like financial APIs. In traditional finance, many of these compositions may be all but impossible.

For example, suppose that one wanted to borrow cash against an equity portfolio at the New York Stock Exchange to short a futures contract on the Chicago Mercantile Exchange. This can be done via a broker who must place collateral on both exchanges and take the risk that the transaction fails. In DeFi, the analogous NYSE loan engine and CME matching engines interoperate on the same blockchain, publicly and openly, each having full visibility into each other’s available transactions and balances. This allows the same process to be atomic – borrowing from one and trading on the other can be done in one transaction, which must succeed or fail – removing the risk, and fees incurred, that would otherwise be held by the broker.

While many innovative financial technology (“FinTech”) companies have built impressive wrapper systems around the existing financial system, these tend to support primarily nonvolatile operations such as read-only data. For example, is the balance of a user sufficient to continue with an ecommerce purchase? While there are certain operations where the wrapper service holds risk, in general, most risk is still borne by intermediaries and issuers. Furthermore, while technology and artificial intelligence have greatly assisted certain capabilities like lending, the end process tends to be far from automated. In DeFi, this automation is integral to the system – volatile operations like trading, lending and derivatives are executed completely without human involvement and oversight.

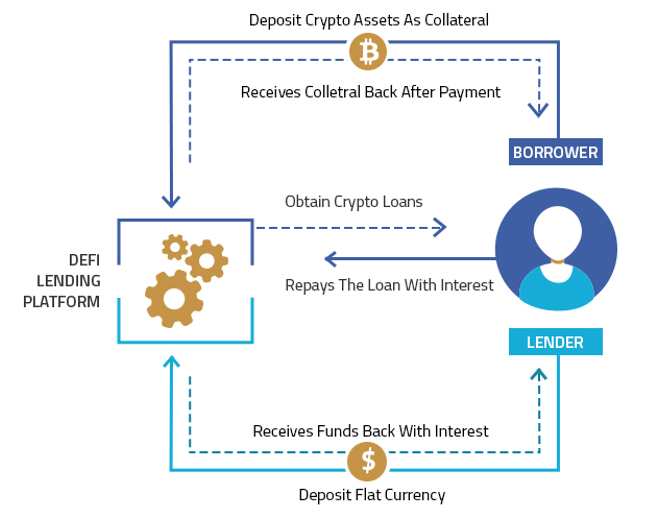

Even with these technological innovations, lending in DeFi currently takes a slightly different shape than its non-crypto-based counterpart. We tend to view lending as a relationship in traditional finance between a lender and a borrower: the lender provides the capital for the loan, and the borrower may provide either some collateral or none at all (uncollateralized). We can further divide lending into loans with recourse, where the lender can pursue additional compensation past the value of the collateral, and those that cannot. Recourse largely depends on the idea of cohesive identity, or some representation of the borrower that can easily be verified but is difficult to create.

The blockchain is open, permissionless and anonymous. Recourse is not an option in crypto; in nearly all cases, it is simple and costless to create a new address. This could be solved with full collateralization, or a one-to-one loan-to-value ratio, by itself. However, cryptocurrencies historically demonstrate high volatility in exchange rates from leveraged speculation and other uncertainties, both between cryptocurrencies and with fiat currencies, or fiat-pegged cryptocurrencies, called stablecoins. Given that liquidation is not an instantaneous or foolproof process, even in DeFi, to hedge against fluctuations in collateral value, most platforms demand loan-to-value ratios greatly exceeding 100%. While this may seem punitive, the overcollateralized loan market sees high demand in crypto due to demand for short-term liquidity, leverage and tax optimization. Firms like Gauntlet help DeFi protocols optimize collateralization requirements to match market conditions, in relation to currency volatility, allowing laxer, and more attractive, requirements in stabler times.

We can view the current lending relationship in DeFi as between a collateralized borrower and the platform itself. Platforms tend to provide two types of associated cryptocurrencies: a promissory token, which represents the loan value, and a governance token, which allows the holder to influence platform decisions and often receive some fraction of platform fees. When a borrower creates a loan on a platform, the platform’s smart contracts retain custody of the collateral for the lifetime of the loan. In exchange, the platform provides a promissory token that can be exchanged for the collateral supplied along with interest. These tokens, which are often pegged at a fixed rate to a fiat or cryptocurrency, can be transferred between parties, but only the original party can redeem for the associated collateral.

There are many attractive characteristics to DeFi, the most important being true transparency and the ability to independently validate ownership and settlement. This transparency makes certain fraudulent actions, like tricking multiple lenders via rehypothecation of already leveraged assets, all but impossible. But while this reduces certain types of risk, it does not entirely remove risk. That leaves us with our fundamental questions: Why is there risk, what constitutes risk in DeFi, and who bears it?

Why is there risk?

We usually view risk in traditional lending relationships separately for the borrower and the lender. For both parties, we can observe three major types of risk: (1) valuation risk, or changes in the valuation of the loaned capital and the loan amount, including interest; (2) opportunity risk, or the likelihood of a better offer being available in the future; and (3) counterparty risk.

While valuation and opportunity risk are important, both tend to be equally knowable, or unknowable, by the lender and borrower in competitive, liquid marketplaces. Counterparty risk, by nature, occurs from informational asymmetry: the borrower and lender have better knowledge of their own side of the bargain than the other. This gap shows up principally in two ways: adverse selection and principal-agent problems.

Adverse selection

In traditional transactions, there is usually an element of adverse selection. A company issuing a new bond, for instance, has better insight into its financial and strategic positioning than those buying the bond. The informational asymmetry between lender and borrower naturally creates lender demand for a trusted third party with material insight into borrowers who can simplify multidimensional, complex risk quantification into a metric that can be compared across borrowers. As a neutral party holding privileged information on the borrower, whether an obligor for a bond issue or a consumer taking a personal loan, this helps to reduce adverse selection encountered by lenders. On the borrowing side, adverse selection is reined in by regulation and free market competition; lenders must compete with each other and must comply with regulations.

Adverse selection in the decentralized financial world looks similar, but not identical. On the borrower side, interest rates are public, open source and verifiable – as lending code exists immutably on the blockchain, there is no question the rates methodology presented maps to the final output exactly. On the lending side, the current state of DeFi means only overcollateralized loans are possible; adverse selection largely becomes a function of proper collateral valuation, which is less of a concern with sufficiently liquid collateral.

The transparency of the blockchain all but eliminates borrower adverse selection as lending standards are fully transparent. However, the platform itself bears increased risk. For example, the existence of public interest rate calculations significantly constrains a protocol’s ability to defensively and rapidly react to adverse market conditions. In liquidity crunches and drawdowns where collateral value may diminish rapidly or many collateralized borrowers may withdraw simultaneously, the protocol may not dynamically adjust rates quickly enough to compensate for incurred losses. Similarly, while the trustless nature of crypto makes it ultimately nondiscriminatory, since protocols underwrite loans based solely on on-blockchain activity, DeFi lending currently does not factor in historical borrower behavioral patterns and may fall susceptible to bad actors.

Principal-agent problem

Many traditional financial intermediaries exist because of the inherent conflict issues that arise when agents can reap asymmetric rewards from risk borne by the principal, either an individual or an entity they represent. In a salient example, the compensation given to fund managers tends to be performance-based – compensation increases as reward for higher returns. However, on the downside, losses are capped due to limited liability. This implicitly rewards riskier decision-making, often to the eventual detriment of the fund’s investors.

This moral hazard often occurs from information asymmetry; the fund manager has free rein to take riskier bets simply because she knows more about the true state of fund investments than the fund’s investors. Objective third-parties, like Moody’s Investors Service, exist to help reduce this asymmetry. By distilling complex, idiosyncratic information into comparable, rigorous risk assessments, this reduces the information gap and helps the principal rein in her agents.

In DeFi, the principal-agent conflict arises through the mismatch in incentives between those who invest in the platform, like liquidity providers or lenders, and those who govern the platform. Much like the shareholders of a large corporation, most platforms’ governance tends to be at the behest of a few active investors with large governance token stakes who usually have an aligned, long-term incentive to promote best practices for the platform’s health. While many platforms pass through risk fully to end users, such as providing an avenue for swapping tokens but not acting as a counterparty, others may assume certain risk to promote platform health.

For example, MakerDAO, the large DeFi platform that oversees the stablecoin DAI, uses the competing DAI Savings Rate and platform stability fees as its primary methods to regulate loan supply and demand, creating and destroying the governance token MKR to satisfy platform treasury discrepancies. This directly impacts the price of MKR, often to the detriment of investors. While this reduces risk to the platform and the DAI-USD peg in normal times by providing a direct mechanism to influence supply and demand, this can increase tail risk when supply and demand become severely imbalanced.

Similarly, for decentralized marketplaces like Ethereum’s Uniswap, improper alignment of governance incentives can break the fine balance between arbitrageurs and liquidity providers, or those who lend assets to allow exchange by automated market makers. Unlike traditional U.S. equities trading, where regulation nearly eliminates inter-exchange price discrepancies via the National Best Bid and Offer system, many DeFi protocols must rely on continual arbitrage activity to maintain market spot-price synchronization. This is not free. Much like traditional market-making rebates offered by some U.S. equity venues, protocols often operate at substantial loss, especially initially, to incentivize liquidity, which in excess can lead to inefficient pricing. If the protocol incentivizes arbitrageurs too much, liquidity providers will disappear, leaving the protocol unable to properly function. Optimizing this balance at regular intervals is crucial to a protocol’s long-term survival.

The governance question is a classic principal-agent conflict: though the platform liquidity providers and users provide its long-term value, the platform’s destiny is principally controlled by a much smaller (in practice) governance body. Exacerbating the problem, as governance tokens trade freely on exchanges, short-term speculators or activist investors can disrupt proper platform governance, reducing stability and jeopardizing long-term health. However, in practice, this tends to be a limited issue, given the largest holders look to create governance token value through long-term platform growth and stability.

Who bears risk?

If we imagine a simple loan, we can clearly observe counterparty risk primarily falls on the lender during the loan’s lifetime. After a borrower receives the loaned capital, at any point in time until full repayment, the borrower can either willingly or unwillingly choose to default, leaving the lender with some amount of loss. This highlights an important point: While the borrower can make a loan based on the lender’s current state, assuming the loaned capital is not dependent on the lender, like fiat currency, the lender must project risk out throughout the loan’s lifetime.

Given the scale of traditional credit markets, there exists significant incentive for both parties to try to achieve the best deal, which comes from properly measuring this risk. In a competitive loan market where many borrowers and lenders exist, this is quantified in the spread on a debt obligation, which reflects the market’s best pricing for an obligation’s risk. This risk can be reflected on the obligor level, which would apply to all debt issuances by the same obligor, or impact issuances asymmetrically; for instance, solvency risk may be more of a concern for issuances with long maturity dates.

We commonly assess risk along two dimensions: probability of default and loss given default. At the obligor level, we can estimate default risk by comparing yield versus the risk-free rate. However, since most debt trades infrequently, using the last traded price may not reflect up-to-date risk information. For publicly traded firms, we can back-derive implied riskiness from equity value, by viewing equity as a call option on the firm’s asset value. This gives us a much stronger real-time approach to forecast a firm’s likelihood to default, and forms the backbone of Moody’s Analytics’ proprietary Expected Default Frequency (EDF) methodology. Alternatively, we can model risk using borrower financial and behavioral information for unlisted firms.

In the current overcollateralized DeFi lending paradigm, we can better understand lending as between an overcollateralized borrower and the platform itself. In most common implementations, a platform usually issues at least two instruments: a governance token, which allows holders to vote on the platform’s governance; and a promissory token, representing the loan’s value, often pegged to another currency.

For the collateralized borrower, counterparty risk tends to be primarily related to the platform properly functioning. In the absence of improper collateral liquidation, such as a platform error or a hack, the borrower can return the promissory tokens received plus accrued interest to retrieve the collateral provided, regardless of the market price of the promissory token. However, even in the case of improper liquidation of certain collateral, the usual first bearer of risk tends to be the protocol itself via its governance token holders.

In many cases, governance tokens serve as a backstop mechanism for shortfalls when DeFi protocols incur losses, including from improper liquidation. Often, protocols will reward governance holders with the burning, destruction or otherwise invalidation of governance tokens by open-market purchase, similar to equity buybacks, when the platform is profitable. In exchange for assuming risk, most platforms additionally reward governance holders with regular dividends from platform-charged fees.

When the platform experiences significant losses or solvency issues, governance tokens can be created, diluting value but infusing the platform with emergency capital. This ensures alignment between the governance token holders and the platform itself – good governance should be profitable for holders, while bad governance should be penalized. However, this also implies a mechanism to gauge risk. Much as we view the equity price of a firm as a strong predictor of future default likelihood, as in the Merton model of credit risk, we can perhaps similarly view the performance of governance tokens as a quantitative measure of the market’s outlook on a given protocol’s risk.

More interestingly, this risk must reflect in the promissory asset as well. While many protocols feature promissory tokens pegged to a certain benchmark, the true value tends to reflect the implicit risk of the underlying collateral. As a rather extreme example, we can again look at MakerDAO. In the most common outcome, if DAI were to stray from its peg, it could be redeemed back for its associated collateral, with no net loss to the collateralized borrower. However, if all collateral in MakerDAO were improperly liquidated, the platform could try to mint and auction its governance token, MKR, to remain solvent and cover the shortfall. In a severe crisis, this may not be enough. The DAI would become worthless, having no collateral to back it, and the collateralized borrower would lose some or all their capital.

Such an event is, however, low likelihood. Even in the depths of the 2020 COVID-19 crash as the most common MakerDAO collateral’s, Ether, value halved in days, the value of the promissory token remained remarkably stable, although it briefly lost its peg.

What is risk and how do we model it?

Despite these risks, interest in DeFi has grown substantially, propelled by promise of the technology to transform financial services. With more institutional investors considering allocating, this naturally implies the need for a consistent methodology in evaluating and quantifying the above dimensions of risk. Given the rapid evolution and proliferation of DeFi, it has been difficult to properly quantify risk. How do we think about risk scoring and modeling in the new paradigm?

Analysis of risk in DeFi protocols can be quite different when compared to traditional finance. The transparency and composability of DeFi protocols allows for a more technical evaluation of risk. For instance, instead of creating VaR models to predict an unknown counterparty’s risk, one can train fine-grained models directly on historical market participant data. The prior trades, transfers, and borrowings of a user are all public and provide direct insight into their behavior. However, the technical complexity of such models is much higher; one must carefully ensure that a model’s mechanics and predictions match the exact execution of the smart contract used. Moreover, there tend to be more principals/agents in DeFi, as we replace a single trusted entity with many untrusted entities coming to a consensus. This means that models need to account for far more variability in counterparty behavior than is usually found in traditional finance.

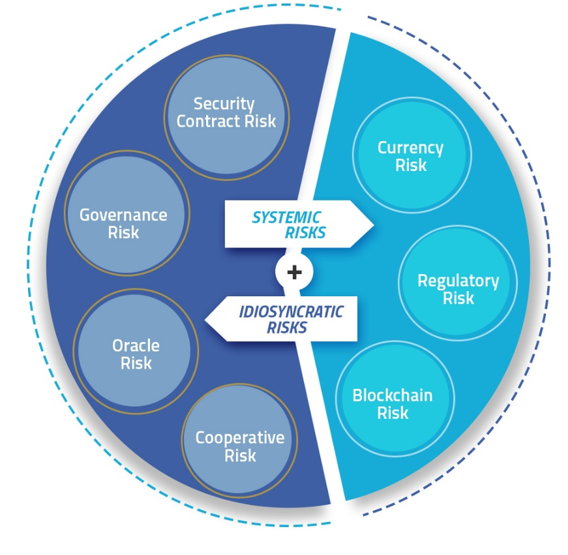

More generally, we can identify several critical dimensions of risk which tend to impact all DeFi protocols, albeit not equally. While an evolving topic, it still largely mirrors the risk found in traditional financial instruments. Broadly, these dimensions can be segregated into systemic risks, or risks that impact a large part or all of the DeFi ecosystem, and idiosyncratic risks, or risks that impact a single protocol or group of protocols. Though idiosyncratic risks by nature tend to be unique to a specific platform, exposure to systemic risk factors may also differ substantially per platform.

Systemic risk factors in DeFi include:

- Currency risk: The crypto-asset market is notably volatile, and exposure to the underlying currency risk and derivative assets, such as protocols built on top of blockchains, comes with significant risk. Similarly, the interconnectivity of DeFi services means measuring the idiosyncratic risk of a singular platform is difficult.

- Regulatory risk: Regulators’ views about and reactions to DeFi are evolving, with little guidance on the space so far. Long term, there remains significant uncertainty about the impact of regulation on DeFi as governments seek to find the right balance between the opportunities created by the technology and the potential risks they pose to the financial system.

- Blockchain risk: While certain platforms span multiple blockchains operationally, the most common platform design uses a singular blockchain for its protocol layer. This creates implicit risk on the blockchain itself. Were the underlying blockchain to be compromised or otherwise abandoned, the platform would similarly greatly suffer.

Idiosyncratic risk factors include:

- Security contract risk: Unlike traditional finance, the final word in DeFi is code. A platform is only as valuable and secure as its smart contract code and quality of its team. There have been several notable hacks in the DeFi space, with estimated losses in the billions.

- Governance risk: DeFi platforms live and die by their governance. From simple parameter tweaks to ensure stability to more complicated maintenance like updates and changes, governance is a major risk factor which can not only impact a single protocol, but can have second-order ramifications on dependent protocols, given DeFi’s composability.

- Oracle risk: For transactions and contracts dependent on off-blockchain events, like changes in price, trusted entities called oracles are tasked to provide the data in a timely, secure way. Oracles can take the form of other smart contracts, other blockchains, or external data sources. However, because of their privileged position, oracles are specifically targeted for manipulation, with potentially catastrophic outcomes. Oracle issues infamously caused more than $120 million in losses for lenders such as CREAM Finance and a nearly as large loss on Aave, which was ultimately mitigated by Gauntlet’s governance proposal.

- Cooperative risk: In the current overcollateralized paradigm, the primary embedded risk in the lender-borrower relationship comes from improper collateral valuation and liquidation. Liquidation is largely decentralized, with platforms relying on third parties to liquidate collateral as-needed in exchange for fees. When the valuation-liquidation mechanism fails, this causes both significant risk and opportunity. This occurred on March 12, 2020 when the MakerDAO collateral auction had a lucky liquidator purchase $8.32 million in collateral value for $0.

This leads to the most important factor in understanding platform risk exposure: mitigation techniques. While all DeFi platforms may depend on similar primitives – namely the existence of a smart contract-supporting blockchain and crypto-accessible collateral – the economics coded into the protocol’s design, the quality of the smart contracts and continued maintenance by developers, and the dynamic tweaking of key parameters by governance holders dramatically impact risk quantification.

While not comprehensive, we can outline best and worst cases for the identified risk factors for an arbitrary platform, along with sample factors which may mitigate risk exposure.

The Future of Crypto Risk Assessment

Given the multidimensionality of risk, consistent risk modeling must consider all of the identified sources of risk for a DeFi protocol – contract, market/currency stability, oracle/external dependencies, governance, regulatory, and cooperation. A cohesive risk assessment framework that enables timely measurement of risk for a particular protocol and allows for a comparison of risks across protocols would help mitigate many of the impediments to further growth and help facilitate informed investment decisions in the space.

As the DeFi and traditional financial systems continue to converge, the solution to this challenge will require a convergence of the knowledge and expertise of both new and established risk assessment providers. Companies like Gauntlet, which specialize in profiling and analyzing user behavior, can build platform-specific models based on the platform’s on-chain lending and trading history. By working directly with the governance teams of client protocols to dynamically tweak important parameters, Gauntlet provides a systematic approach to managing platform stability, reducing both governance and cooperation risk.

While DeFi presents both new opportunities and new risks, it aims to solve the same market needs for capital and services as the traditional financial ecosystem, and largely to benefit the same participants. By drawing on these parallels and the established expertise and risk assessment capabilities of Moody’s Analytics, we can design a brighter, safer future for this exciting, rapidly evolving space. Both Gauntlet and Moody’s Analytics look forward to engaging with the market in a dialogue around the development of a risk assessment framework.